Naoki Nagayama Photo Exhibition

The Starting Gate to the Future

– The Days of the Former Okinawa Juvenile Training School

- Dates

- Friday, July 29 - Thursday, August 11, 202211:00~18:00

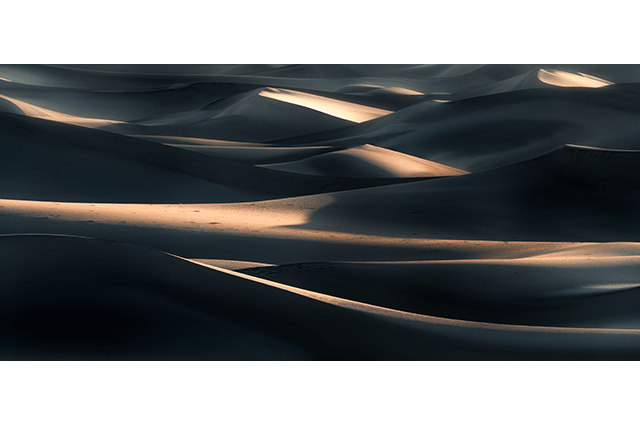

A “Series” of Montages of Light and Shadow

Commentary on Naoki Nagayama's “Embarked” Photos

It used to be prohibited to release information on what goes on

inside of Japan's Juvenile Training Schools. But, by chance, all of

that miraculously changed. The trigger came, as Naoki

Nagayama explains, “With planning underway to relocate the site

I was working at to new premises, the director proposed that I

photograph the former site with the understanding of my

colleagues as a kind of record.”

So began a rare inside look into the facilities and daily life of the

detained youth, a year and a half before the former Okinawa

Juvenile Training School was moved in 2018. What should be

pointed out is that permission to photograph inside the school

was granted on the grounds that certain rules would be observed

out of consideration for security matters and personal

information. Though that placed restrictions on photographic

activities, Nagayama shifted the visual paradigm by weaving

those confines into a unique process of photographic storytelling

that I dare call “views from behind” and “ideas of windows and

oblique lighting” that descend into the depths of the mind.

For example, the lonely silhouette of the person at a desk by the

wall reading to oneself, the scenes of practice for field day, and

the youth clad in red work clothes and caps exiting the front

entrance or dressed in blue doing gardening work are all taken

from behind, while the articulate montage of profiles of the youth

seen through the window during meditation juxtaposed with the

outdoor surroundings, the shadow of the latticed window cast

upon the dimly lit wall and blue staircase inside by the incoming

light and the scratchy graffiti etched in the window pane with a

sharp instrument seemingly use the language of shadows to

convey what kind of place this was.

Juvenile Training Schools are recognizable by their high walls

topped with wire mesh fencing, but what stirs the unconscious is

that this wire fencing faces downward to the inside of the

compound. Overtly suggestive of the isolation and imprisonment

of social will, the walls and fencing are captured in many of the

photographs like a defining mark. And, even if unintended, these

walls and the inward posture of the fencing recall the perimeter

enclosures surrounding the massive US military bases that have

reshaped the Okinawan landscape. Only that, opposite to what

you see at the Juvenile Training School, the fencing atop the base

enclosures leans outward, telling you that the imprisoned are the

Okinawan people.

In the walls, bars and corridors of the 60-year-old buildings are

seen countless traces of discipline and training, introspection and

rebirth. Nagayama has tried to reveal and herald those vestiges

from a quiet approach.

To think that the very first photos Nagayama ever took were

evening shots of hibiscuses illuminated by streetlamps, he has

crossed into new territory here as “delinquency” is purportedly

what has blossomed. That apart, these untitled montages of light

and shadow come together like a series. Each time the detained

youth turn their backs, it's like Nagayama's photos, which began

by chance as a form of photographic record, embark on a new

journey.

Isao Nakazato (Critic)

Naoki Nagayama Profile

Born in Okinawa Prefecture in 1967. Picked up a digital camera to take photos for his blog Ryukyu no Kaze as an FC Ryukyu fan. Took shots of hibiscuses illuminated by streetlights with a single-focus lens camera borrowed from a fellow fan, thought he might be able to be a photographer, and started taking photos.

- 1967

- Born in Okinawa City, Okinawa Prefecture.

- 1995

- Worked for Naha Juvenile Classification Home.

- 2010

- Started taking photos.

- 2010

- Transferred to Okinawa Juvenile Training School.

Selected for the JPS (Japan Professional Photographers Society) Exhibition.

Fourth place in the Photo-con School Freedom Division Annual Award of the Monthly Photo Contest Magazine published by the Nihon Shashin Kikaku publishers. - 2013

- Fragments 3: Wings Fragment, “Where I Was,” Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum.

- 2013

- Solo Exhibition, "Two-person Exhibition: Shooting," Naha Civic Gallery.

"Daido Moriyama Endless Works North/South" Exhibition Related Events in the "BUCK"

Portfolio Review Exhibition, Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum. - 2014

- Fragments 4: Wings Fragment, "Miz," Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum.

Photo Solo Exhibition, Collective Fragments 5: "Masako,"

Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum. - 2018

- Solo Exhibition "In My Juice," Gallery Runrun.

- 2019

- Selected for Exhibition of the Nikakai Association of Photographers.

- 2021

- Photobook of "The Starting Gate to the Future" published by Ribbonsha.

Photo Exhibition, "The Starting Gate to the Future," at INTERFACE-Shomei Tomatsu Lab.

This exhibition looks inside the former Okinawa Juvenile Training School just before the facility was relocated to new quarters in 2018.

The original youth detention and rehabilitation center was established in Koza City as the Ryukyu Juvenile Training School in 1960 by the Government of the Ryukyu Islands. Okinawa at the time was under rule of the US Military. It was a turbulent period fraught with riots and tensions stemming from the numerous incidents involving the US Military and social unrest. The rebellious youth who were sent to the school were in many ways a reflection of Okinawan society of the time. Physical violence against staff and escapes en masse were almost everyday events. Of particular note, there were three successive cases of violence in April 1963 where the youth who were attempting to escape set fire to the school, which required not only the police and fire department but also US MPs to be called out to quash the uprising. Overcrowding and inadequate facilities were blamed as the underlying causes. Though measures were taken thereafter such as to replace fencing with walls, a contentious mood persisted until recent years.

The facility was renamed the Okinawa Juvenile Training School when control over the islands was returned to Japan in 1972.

You might wonder: What is life like for the detained youth? What training do they receive? Why are they there in the first place? Can the school really rehabilitate them? Do habitual offenders that rampaged society quietly submit themselves to learning? It is a world of many unknowns. But, by a stroke of luck, I was allowed to take photos inside the facility, which led to this opportunity to show you a little bit of what goes on inside the walls.

The detained youth obviously ran into some sort of trouble on the outside, which is why they are there. But, life on the inside can be just as hard, if not worse, in many ways. Yet, through my contact with them, I have found many of these detainees to be not so different from ordinary kids.

There isn't anything decisively unique about the detained youth. When you go one-on-one with them, amidst the strict moments or cuddling you do, you begin to see the person inside them. By that, I mean how they can be kind and are really like any other kid, which they themselves have forgotten. The key to rehabilitating them, you see, is to get them to remember that.

From the tumultuous days of the Ryukyu Juvenile Training School through the lesser so of present Okinawa Juvenile Training School, many a troubled youth have embarked on a new journey from here. Though we are in a new location and the times are different, my feelings from the years of the Ryukyu Juvenile Training School haven't changed: my hope is that those who make it out of here find happiness and are no longer driven by what made them into the menace to society that landed them here in the first place.

Naoki Nagayama